Danse Macabre #16: Film Review — "Willard" (1971)

In 1981, Stephen King published Danse Macabre, a work of non-fiction wherein the author acts as a tour guide through the history of horror. He addresses the social issues and political conflicts that have influenced creators over the years, and the ways creators have influenced each other.

King closes out the volume by recommending 96 films and 113 books released during the 1950-1980 period that he feels have significantly contributed to modern genre fiction. With this Fearsome Queer column, I’ll be making my way through those titles in no particular order.

Willard Stiles is quite a notorious figure. Even horror fans who haven’t seen the movies know he’s the guy with killer rats for pets. I became familiar with him thanks to the trailer for the remake that aired profusely on TV when it came out in 2003. I recall elevator doors opening and unleashing a flood of vicious rodents, in a brazen tribute to The Shining, with pale-ass Crispin Glover in the middle of ’em all, surrounded up to his shoulders, lookin’ like Hop Topic Snow White. Whereas the remake is more visually and tonally audacious, albeit kinda goofy, the original is surprisingly tame, and Bruce Davidson’s depiction of the character is softer and decidedly less campy (and dare I say brilliant). All things considered, for much of the runtime, Daniel Mann’s 1971 version of Willard feels more like a fucked up drama than a straight-up horror picture.

I suppose that is to be expected when you give a script like this to someone who made a name for himself mounting plays by Tennessee Williams and William Inge on Broadway. Daniel Mann’s résumé is pretty fascinating, actually. In the 1940s, he became one of the original teachers at the Actors Studio and a top “actors’ director” for the New York stage. Then, after pivoting to Hollywood in the ’50s, he directed seven actors to Oscar nominations in just eight years; three of them won (two of them deservedly). In the ’60s and ’70s, his career took a serious dip, directing notable stars in non-starter after non-starter. But amid that slump, Mann helmed this weird little gem.

Although Mann and Willard may not seem like the best fit, his stagecraft shines anyway. He excels in particular at setting up a wide shot and using the entire three-dimensional space to block the action; too few film directors possess this skill. A prime example is a scene in which one of Willard’s coworkers is closing in on his rats’ hiding spot within their office. Throughout the scene, Mann shows us the whole soul-draining workplace where Willard works, and each area is consistently active, with folks coming and going and moving about as they do their jobs. The suspense of the scene balloons as we, who know where the rats are, notice one particular busybody—amid everything else going on in the shot—snoop nearer and nearer to Willard’s secret. Another director may’ve used a bunch of close-ups and quick cuts to emulate the tightness of the moment, but Mann knows that smart blocking in a wide is just as effective, if not more—if you can direct the eye of the audience.

Mann’s methods work because he spends so much time focusing on character. Of course, the person we spend the most time with is Willard, played in this version by Bruce Davidson. At this point in his long and storied career-to-be, Davidson was only two years removed from his debut in Last Summer, a fucked up indie that I’ll be covering at some point for this column. Davidson plays Willard in earnest, which aligns with the rest of the film. With just a few notable flourishes, Mann’s overall direction, though competent, isn’t outwardly stylish or atmospheric, so Davidson doesn’t need to über-perform like his successor in the dialed-up remake. He can just be real. Davidson makes it easy to relate to his Willard, despite the macabre circumstances surrounding him. Had Davidson delivered a Glover-esque portrayal, that wouldn’t be the case, nor would it have fit. This Willard broods in a more reticent manner; his pot doesn’t start out roaring—he simmers for a while. But once he reaches that boiling point, Mann finally ramps up the visuals.

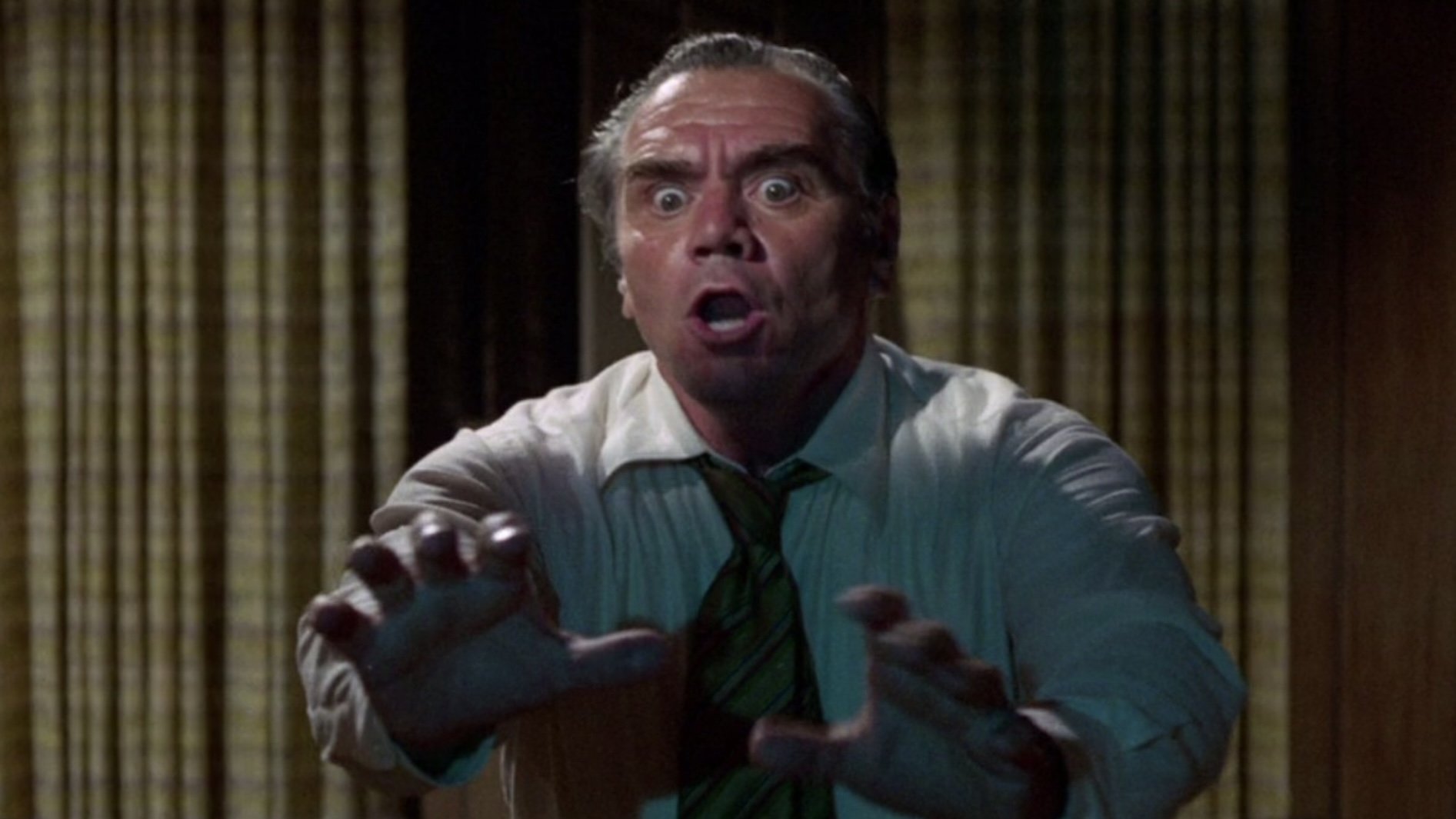

We know very early on that sooner or later Ernest Borgnine, who plays Willard’s dickhead boss Mr. Martin, is gonna get what’s coming to him, but Mann makes us wait. It takes a good chunk of the runtime to see Willard’s rodent army rain hell upon Martin. The lighting gets moodier, and the rats leap and pounce in a way I doubt real-life ones can. But ya know what? Fuck it! In my opinion, more of the movie should’ve been like this. For as notorious a character as Willard Stiles is, I was surprised by how little murder there is in the original, but Mann definitely tells the story well, and he shoots it appropriately for the film he set out to make. So, while I’ll concede that I—speaking purely for personal taste—wanted those little bastards to tear more motherfuckers up, I get and respect what Mann delivered instead.