Danse Macabre #9: Book Review — "The Lottery and Other Stories"

In 1981, Stephen King published Danse Macabre, a work of non-fiction wherein the author acts as a tour guide through the history of horror. He addresses the social issues and political conflicts that have influenced creators over the years, and the ways creators have influenced each other.

King closes out the volume by recommending 96 films and 113 books released during the 1950-1980 period that he feels have significantly contributed to modern genre fiction. With this Fearsome Queer column, I’ll be making my way through those titles in no particular order.

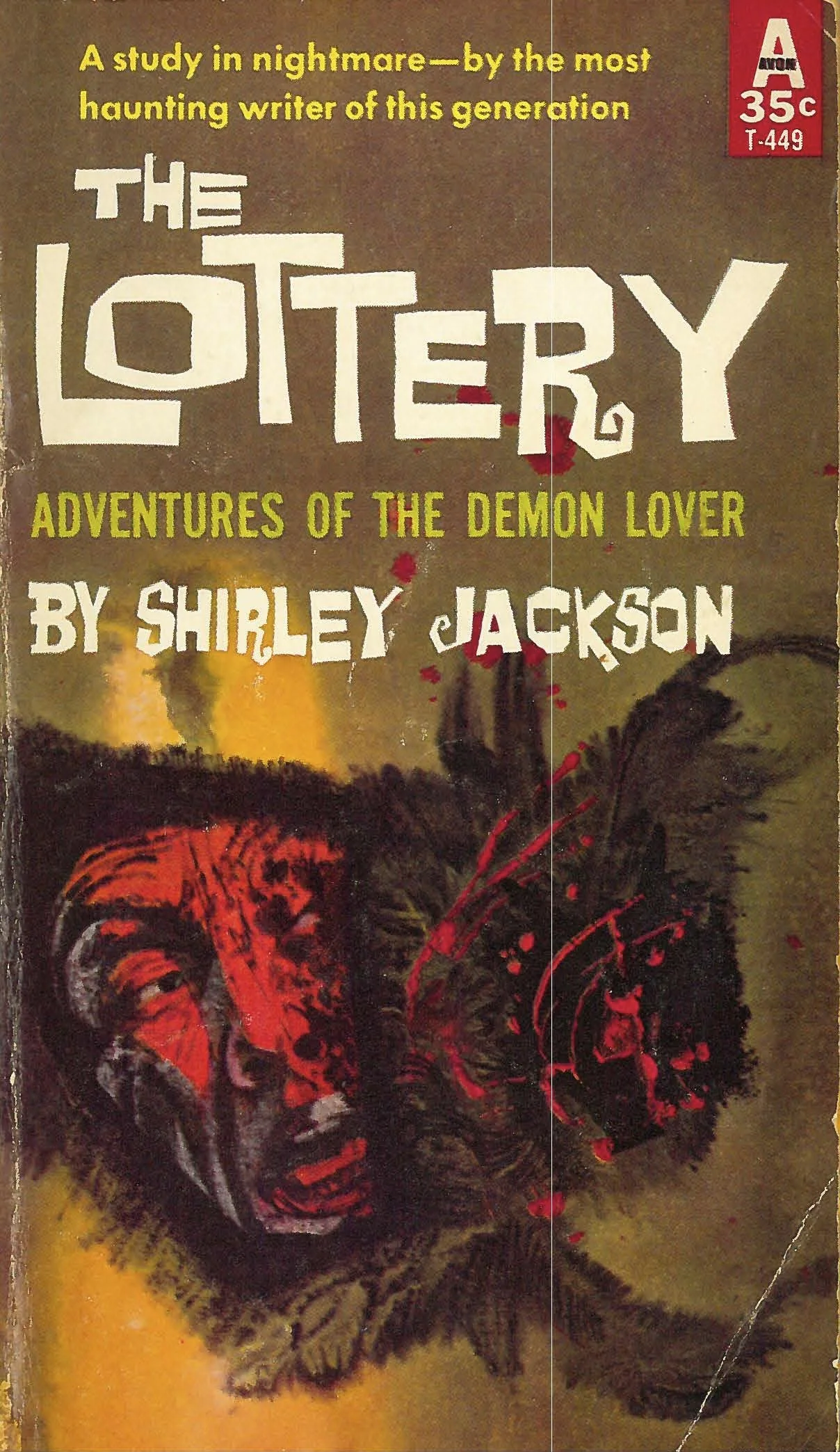

To your everyday casual-to-staunch bibliophile, Shirley Jackson’s name is probably most closely associated with two titles: The Haunting of Hill House and “The Lottery.” Whether they’ve read either masterpiece or not, her name is intrinsically bound to them. It’s like knowing that Charles Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol or that William Shakespeare wrote Romeo & Juliet. People just know, one or the other, if not both. A lot of folks, myself included, were assigned “The Lottery” in school; it’s thematically rich and intricately crafted. It’s also somewhat of an outlier among the rest of the short tales contained within The Lottery and Other Stories. None of the others are quite like it, although many of them are a bit like it. So, when you read the collection as it’s chronicled, you come to realize that “The Lottery” is a perfect finale because it demonstrates an amalgamation of Jackson’s strength as a writer.

Thus, it was pretty savvy of Shirley Jackson to curate the title story last. These days, it is without a doubt her most widely read short story—hell, it might even be more read than The Haunting of Hill House, given how many of us are made to read it for class. The prose throughout the Other Stories appears unassuming at first, then reveals its sneaky complexity once the final punctuation mark has struck, leaving the reader with an unnerving sense of disquiet. While there’s often an air of looming dread or feelings of dismay toward things to come, few of these tales present as outright horror—but I think that makes the collection more interesting, actually! Shirley Jackson has a penchant for finding terror within the mundane, within the tedium of domesticity, in a just a handful of pages.

In fact, two are a mere three pages, and they are both excellent studies in economy. “Got a Letter from Jimmy,” the penultimate entry, is about the clashing neuroses of a husband and wife over something as ordinary as receiving a letter from someone with whom one holds a grudge that the other finds “silly.” One is determined to send the letter back unopened, whereas the other is at their wits’ end to learn what the letter says, and it’s glorious… “Colloquy” is the first of the three-pagers, and it’s the centerpiece of the collection—smackdab in the middle. It’s a conversation between an “upset” housewife and a doctor who is not her usual doctor (because her usual doctor might talk to her husband, which is scary in itself). She fears the world is going mad, or that perhaps she is the one going mad. In truth, times are probably just changing, as times are wont to do, but that simply does not compute with static homemaking routines and traditions.

For Jackson, the city is an alluring yet just as perilous place. “Pillar of Salt” is about a woman vacationing in the city and being driven to madness during her trip. Margaret’s once wide-eyed view of NYC turns sour when she thinks the building she is in is on fire (it’s not) and no one will pay her any mind when she tries to warn them. Later, she encounters some severed limbs. And then it’s all downhill for Margaret to the point that she can’t even cross the street without having a nervous breakdown… “Elizabeth,” the longest story, follows a woman who lives in NYC and works for a boutique literary agency. Years ago, she moved there with big dreams, but, without support and guidance, she became a victim of the soul-crushing hustle and bustle environment she sought. Now she’s middle-aged, dissatisfied, and only pictures a better life—because she’s too wrapped up in the web she’s spun to cut herself loose and achieve it. Her fantasies involve a man named James Harris, who’s no stranger to the reader at this point.

Mr. Harris’ name first appears in “The Daemon Lover,” as Jamie Harris. He is the fiancé of the protagonist, and it’s the day they’re to wed. But he’s missing. He was supposed to pick her up in the morning, but never showed. She goes in search of him, but no one has a clue who she’s looking for. So, we’re left to wonder: did this man dupe her and stand her up on their wedding day, or was Jamie a figment of her imagination the whole time… While the former could certainly be true, “The Tooth” points toward the latter. In “The Tooth,” Clara meets Jim Harris while traveling via bus to seek treatment for an excruciating toothache. After she arrives, she keeps seeing him, and her sightings get increasingly more bizarre. Was Clara always unstable, or has the pain and medication altered her perception of reality? Was Jim Harris real when she initially met him on the bus, or was he always make-believe? Regardless of whether he’s real or fake, Mr. Harris has thoroughly fucked her up! In her break from reality, Clara discards belongings that are tied to her identity.

While Clara purposefully throws away her stuff, one of my favorite entries in this collection explores the horrors of one’s things be stolen. “Trail by Combat” is the fourth segment, and it’s when I knew I was really going to like this book. With her husband away in the Army, Emily lives alone in a furnished room in a building made up of similarly furnished rooms. One day, her possessions start vanishing. Her investigation eventually brings her to the culprit’s open door, where she sees a mirror image of her own home and learns that not only are the apartments identical—they all have the same key. Essentially, any resident can enter any unit anytime! And take anything they want! For me, this is when the meaning of “horror of the mundane” hit me. There’s nothing frightful per se in “Trial by Combat,” yet I found the final reveal utterly terrifying: Emily’s final exchange with the thief left me with chills. And I’m not even that attached to my own stuff!

Jackson sagely uses “stuff” to develop several of her characters. “The Villager” offers great examples of this. Miss Clarence, we gather through the narration, moved to NYC from upstate to be a dancer, but found her place as a stenographer and private secretary, living now as a die-hard resident of the Village where she is an avowed aficionado of the arts. That’s the biographical info Jackson tells us. She then, through things, shows us who Miss Clarence is. Sitting at a soda counter in the opening paragraph, we see that she has a copy of “The Charterhouse of Parma, which she had read enthusiastically up to page fifty and only carried now for effect.” On the next page, she stops to light “another one of her cigarettes so as to enter the apartment effectively.” Life is a show and everywhere Miss Clarence is seen is her stage. Of course she wants a glamours cig—she’s a star! Of course she reads carries around 19th century French lit—she’s cultured! Jackson need not say more.

After you’ve made it through these stories and the rest, you come to “The Lottery.” “The Lottery” combines so many of the elements that Jackson stories are known for: there’s an underlying horror, the conventions of community life are criticized (to put it lightly), and there’s a twisted irony to it all. The town and its citizens appear friendly, kind, and tranquil on the surface. Children frolic, wives gather, everyone knows everyone. But it’s not entirely what it seems… A brutal and deeply fucked up town tradition is due to happen. This idyllic locale is about to select a resident at random to murder, as a group. Fun! And most of the characters are just cool with it? Like, this is just a totally normal thing to do?

Jackson, through the character of Mrs. Hutchinson, shows how complicity can lead to hypocrisy once circumstances change. At the beginning of the story Mrs. Hutchinson feels pretty blasé toward the lottery. It’s not a big deal. We pick a name, we kill them, we carry on with our errands. Until… someone from her family is in danger of “winning.” Then, all of sudden, Mrs. Hutchinson has a problem with the procedure. It’s not fair, it’s not well managed, etc. Although the selection process is as randomized as can be, she bemoans that it’s all “unfair.” And well… she’s got a point! People shouldn’t be sentenced to death because their name was drawn from the proverbial hat. But… she didn’t mind before!

Mrs. Hutchinson cannot fully articulate in the moment why she finds the ritual to be so unjust all of a sudden. She just does. (And she’s not wrong.) Likewise, the town can’t really explain why it is okay, either. It’s just the way it’s always been, so how could be wrong now?! The power of conformity has bound the townspeople to this insane practice, so to stop doing it now would be preposterous, surly, right?! Jackson is basically saying that just because something is the way it is, that does not mean that it should be the way it is—that we should not just go along with something because everyone else is, or because past generations did.

“The Lottery” is so brilliant. The above paragraphs are the tip of the iceberg. Thinking about this story reminds me of why I considered becoming a lit teacher way back when, and it’s making me regret not going into academia in general. I could pick apart Shirley Jackson’s writing all day. (Someone invite me onto their podcast!) So, if you’ve only ever read “The Lottery,” it is very much worth digging into the entire collection. The first twenty-five tales gave me a whole new appreciation for the titular grand finale. I could get further into it, of course (and, believe me, I want to), but I’ve weighed this review down enough (this review probably reads a dash too much like a homework assignment, but oh well). I see why King includes The Lottery and Other Stories in Appendix II. It may not be flat-out balls-to-the-wall horror, but it is horror nevertheless.